De-mystifying Agentic AI: Building a Minimal Agent Engine from Scratch with Clojure

To truly understand a system, you must be able to build it from scratch.

If 2023 was the year of “Wow, it can talk,” and 2024 was the year of RAG (Retrieval-Augmented Generation), 2026 has undeniably become the year of Agentic AI. We are witnessing a fundamental shift in how we interact with Large Language Models (LLMs). We are moving from passive chat interfaces where we ask for information to active systems where we ask for results.

The industry signals are clear. Major tech players are pivoting from simply serving tokens to serving “actions.” The ability of an AI not just to predict the next word, but to use a tool, query a database, or execute a multi-step plan, is the new frontier. As an engineering leader, I see this not just as a feature update, but as a new architectural paradigm. It is no longer about “search”; it is about “work.”

Peeling the Onion: My Experience with LangGraph

Like many of you, I wanted to get my hands dirty. I started experimenting with LangGraph (and LangChain before it). It is a powerful ecosystem. It handles state, cycles, and persistence remarkably well.

However, as a software engineer with over 20 years of experience and a specific love for the simplicity of LISPs, espacially Clojure, I often found myself fighting the abstractions. Python-based frameworks, while robust, often suffer from “Class Explosion.” There are factories, managers, and wrappers that sometimes obscure what is actually happening.

I adhere to a simple rule: To truly understand a system, you must be able to build it from scratch.

I didn’t want the “magic.” I wanted to see the gears. So, I decided to step back from the heavy frameworks and build a minimal, functional, agentic engine using Clojure. My goal was not to replace LangGraph, but to de-mystify it.

What Does an Agent Framework Actually Do?

When you strip away the branding, the fancy class names, and the marketing fluff, what is an Agent Framework?

At its most fundamental level, an Agent is simply a control loop.

It is a software architecture that orchestrates a conversation between a User, an LLM, and a set of Tools. The simplified flow looks like this:

Input: The user gives a goal.

Reasoning: The framework sends this goal (plus conversation history) to the LLM.

Decision: The LLM returns a structured response (usually JSON) deciding whether to answer directly or to call a function (a “Tool”).

Action: If a tool is called, the framework executes the code.

Observation: The result of the code is fed back to the LLM.

Loop: The process repeats until the goal is met.

That’s it. It is a while loop with some JSON parsing.

The “Value Add”: Why Do We Need Frameworks?

If it is just a loop, why do frameworks like LangGraph, CrewAI, or AutoGen exist? Why don’t we just write a while loop in Python or Java and call it a day?

Because “production-ready” is hard. A robust framework provides the necessary scaffolding to turn that simple loop into a reliable system. Specifically, they solve these four problems:

Abstraction (The Adapter Pattern): They normalize the differences between models. Switching from OpenAI to Anthropic or a local Llama model shouldn’t require rewriting your entire codebase.

Memory Management: An LLM has a limited context window. Frameworks manage conversation history, summarizing old messages or storing them in vector databases to prevent “amnesia” or token overflow.

Structured Output & Error Handling: LLMs are non-deterministic. They make mistakes. Frameworks include “guardrails” to validate that the JSON returned by the model is actually valid, and if not, they ask the model to fix it (Self-Healing).

Tooling Standards: They provide a standard way to define tools so that the LLM understands how to use them reliably.

In this article, we are going to build these components one by one, using the data-driven philosophy of Clojure. We will start with the loop, and we will end with a minimal graph-based agent engine.

The Core Loop (Pure Functions over Objects)

In many Python-based frameworks, creating an agent starts with instantiating a class, perhaps inheriting from a BaseAgent, and setting up state managers. In Clojure, we strip this down to the essentials. An agent is not an object; it is a recursive function that transforms data.

We need two things to start: a way to talk to the LLM and a loop to maintain the conversation state. We will use clj-http for the network and jsonista for high-performance JSON handling.

Here is the absolute minimum viable “brain” for our agent using Ollama + gpt-oss:20b:

Let’s break down what is happening here, referencing the numbers in the code:

[1] Stateless Design: Notice that

call-llmdoesn’t know anything about the past. It just takes a list of messages and returns a response. This makes testing incredibly easy compared to mocking complex objects.[2] The HTTP Call: We send a standard POST request. The complexity of the LLM is hidden behind this simple HTTP interface.

[3] JSONista Decoding: We use

jsonistato parse the response and mapping keys to keywords for idiomatic Clojure map access later on.[4] The Loop: This is the heart of the engine. Instead of a

MemoryManagerclass, our state is simply thehistoryvector passed into theloop.[5] Recursion: In Clojure, we don’t mutate a list

history.append(response). Instead,recurcalls the loop again with a new history vector that includes the latest response (conj). This immutability ensures that we can always trace exactly how the state evolved without side effects corrupting our data.

At this stage, we have a chatbot, not an agent. To make it “agentic,” it needs to do more than just talk, it needs to structure its output so we can act on it.

Taming the Chaos (Structured Output & Self-Healing)

A loop that produces text is a philosopher; a loop that produces structured data is an engineer. For our engine to become “agentic”, to actually call tools or query databases, we cannot rely on chatty responses like “Here is the data you asked for...”. We need raw, valid JSON.

However, LLMs are probabilistic, not deterministic. They make mistakes. They forget brackets. They return strings when we ask for integers. In Python frameworks, this is often handled by complex “Output Parsers.” In Clojure, we have a superpower: Data-driven schemas.

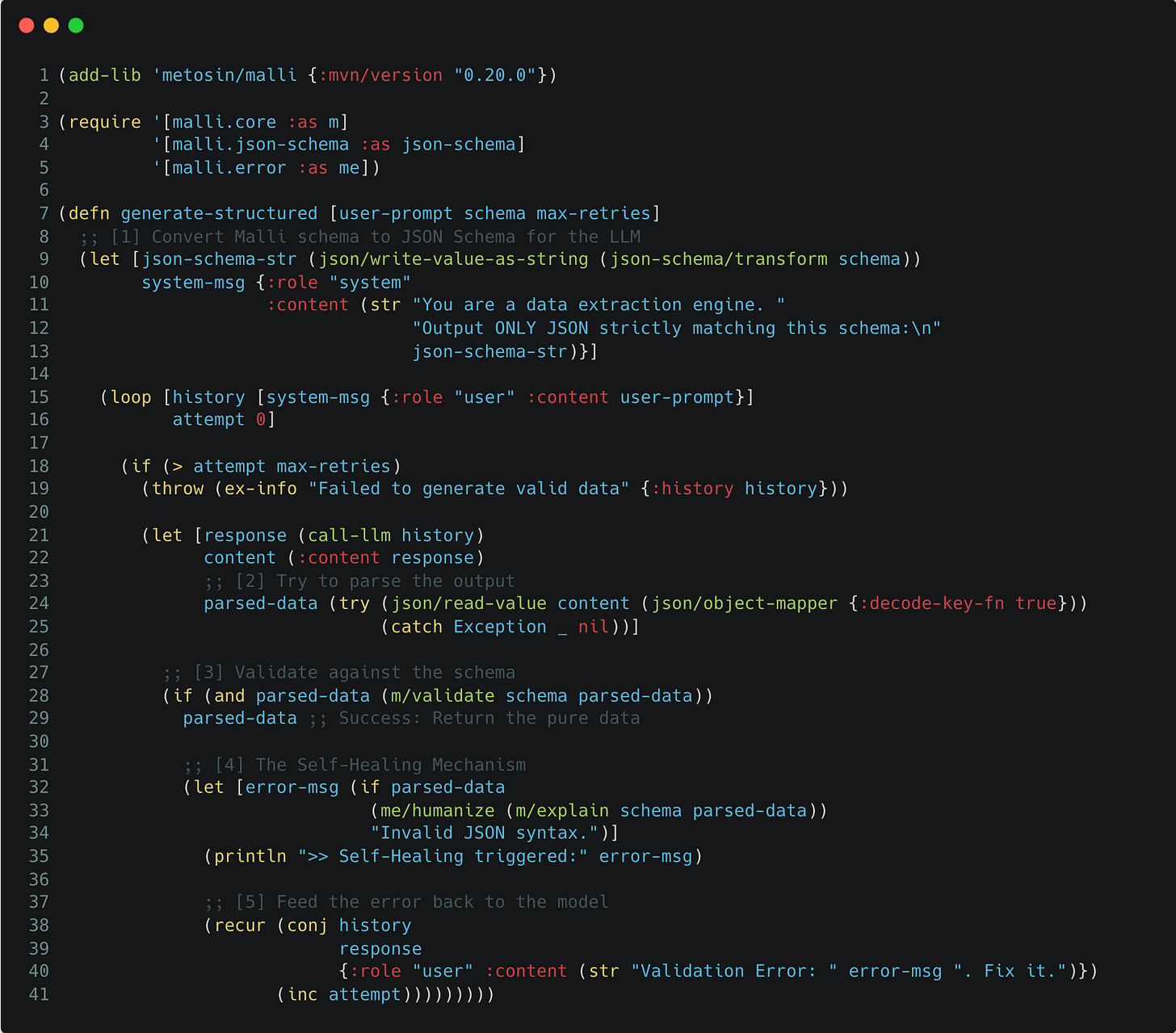

We will use metosin/malli to define exactly what we want. But we will go a step further. We won’t just hope the model gets it right; we will build a Self-Healing Loop. If the model’s output doesn’t match our schema, we won’t crash. Instead, we will feed the validation error back to the model and say, “You made a mistake here. Fix it.”

Here is how we implement structured generation with self-correction:

Let’s unpack the mechanics:

[1] Speaking the Lingua Franca: LLMs don’t natively understand Clojure code, but they are excellent at understanding JSON Schema. We use

malli.json-schema/transformto convert our internal Clojure specs into a format the model understands, injecting it directly into the system prompt.[2] Safe Parsing: The model might return broken JSON. We wrap the parsing in a

try-catchblock usingjsonista. If it fails,parsed-databecomesnil.[3] The Contract: We use

m.core/validateto check if the data strictly adheres to our schema. This is our gatekeeper. Nothing passes unless it matches the spec.[4] & [5] Closing the Loop: This is where the magic happens. Instead of throwing an exception and giving up, we calculate the exact validation error (e.g., “Missing key: :price”). We then treat this error as a new prompt, append it to the conversation history, and recurse. The model sees its mistake and almost always corrects it in the next turn.

This simple function turns a “creative” LLM into a reliable “data processing” component. Now we have a brain that can think (LLM) and a mouth that speaks clearly (Structured Output). In the next part, we will give it hands to do work.

The Graph Engine (State Machines without the Boilerplate)

If you look at the source code of complex agent frameworks, you will find layers of abstractions: StateGraph, CompiledGraph, Pregel, etc. But if we strip away the complexity, an Agent workflow is just a Finite State Machine (FSM).

Real-world tasks are rarely linear. You don’t just “Write Code.” You “Plan” -> “Write” -> “Test.” If the test fails, you go back to “Write.” This cycle is what separates a simple script from an autonomous agent.

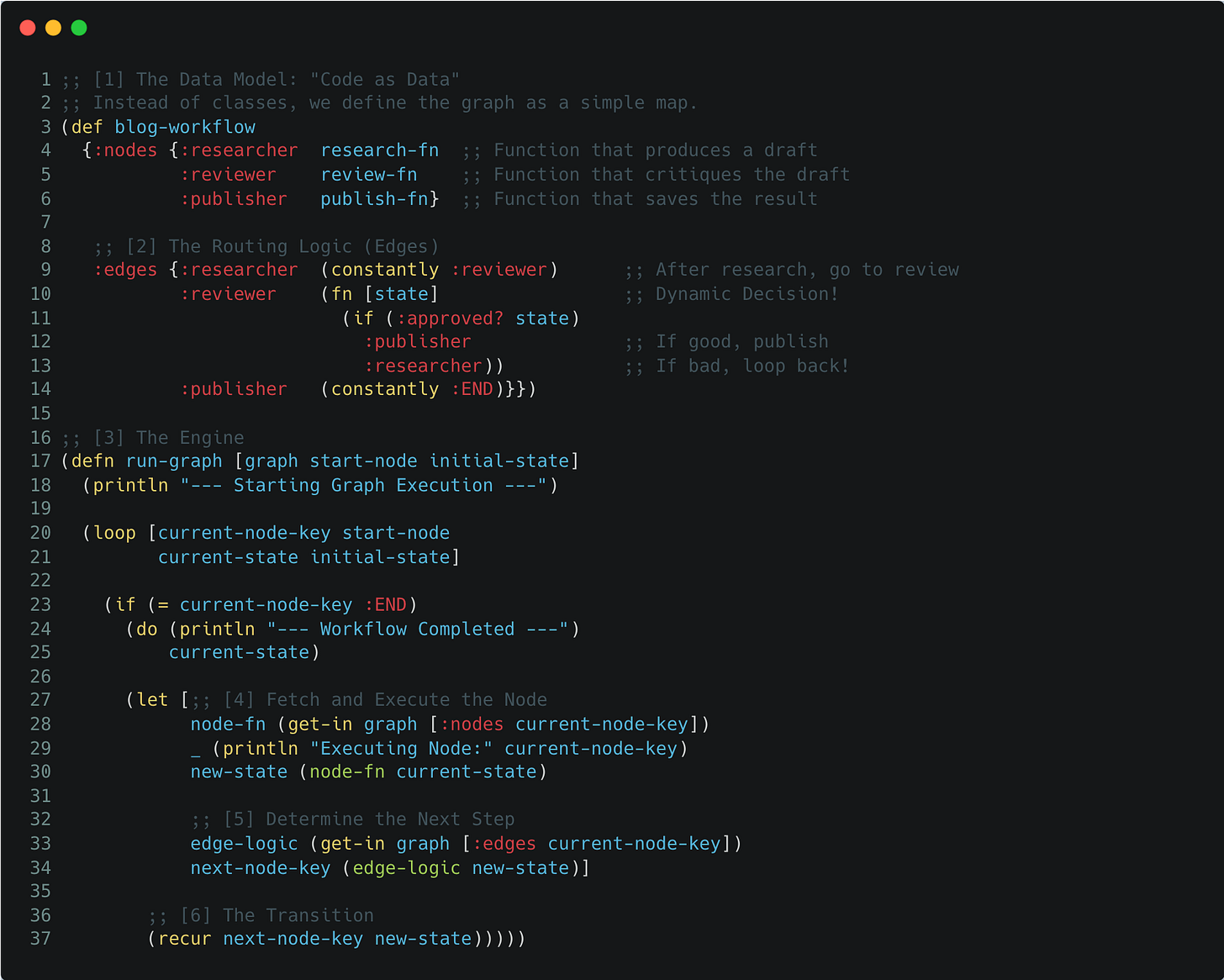

In Clojure, we don’t need a heavy framework to model this. We just need a Map to define the structure and a Loop to drive the engine.

Here is how we build a graph engine that supports cycles and decision-making in under 20 lines of code:

Let’s break down the mechanics:

[1] The Graph as a Map: We don’t need a

GraphBuilderobject. The graph is just data. This makes it readable, portable, and easy to visualize.[2] Dynamic Edges: Notice the edge for

:reviewer. It is not a static link; it is a function. This is the “Brain” of the flow. It looks at thestate(did the draft pass?) and decides where to go next. This enables the Self-Correction Loop.[3] The Engine: This function is generic. It doesn’t care if you are building a blog writer or a coding assistant. It just takes a map and runs it.

[4] Node Execution: Each node is a pure function that takes

stateand returnsnew-state. This makes individual steps easy to unit test.[5] & [6] The Recursion: Once a step is done, the engine consults the

:edgesmap to find the next key andrecurs. The state flows through the system like water through pipes, accumulating data as it goes.

By combining the Structured Output (to make reliable decisions) with this Graph Engine, we can build systems that don’t just guess they work, check their work, and fix it if necessary.

In the final part, we will add the missing piece for production systems: Observability. We need to see inside the brain of the agent while it runs.

X-Ray Vision (Observability) & Conclusion

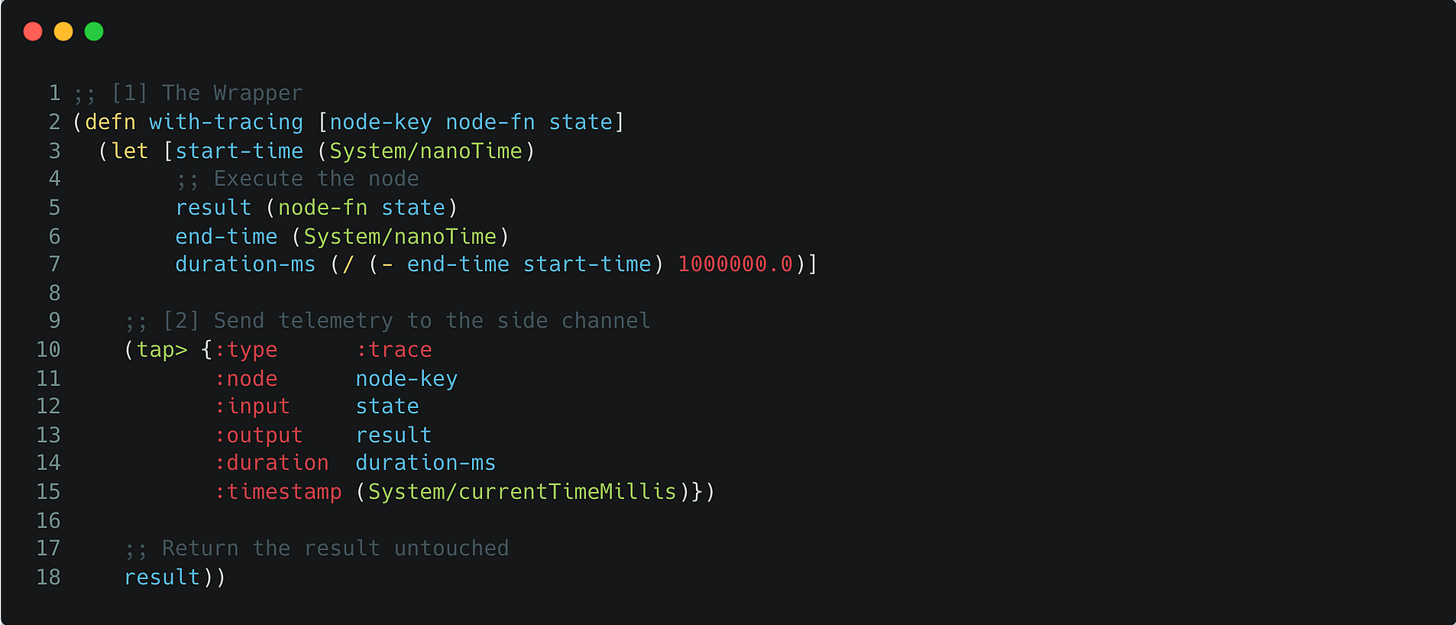

An autonomous agent is a black box. It takes input and (hopefully) produces output. But when it loops infinitely or hallucinates, you need to know why. Standard logging (println) is messy and intrudes on your business logic.

In the Java/Python world, setting up OpenTelemetry usually involves complex configuration and agents. In Clojure, the language itself gives us a native mechanism for this: tap>.

tap> allows us to send data to a “side channel” without affecting the main flow of execution. It is like putting a wiretap on your code. We can inspect the flow of thoughts, inputs, outputs, and latency without changing a single line of our core logic.

Here is how we wrap our graph nodes with X-Ray vision:

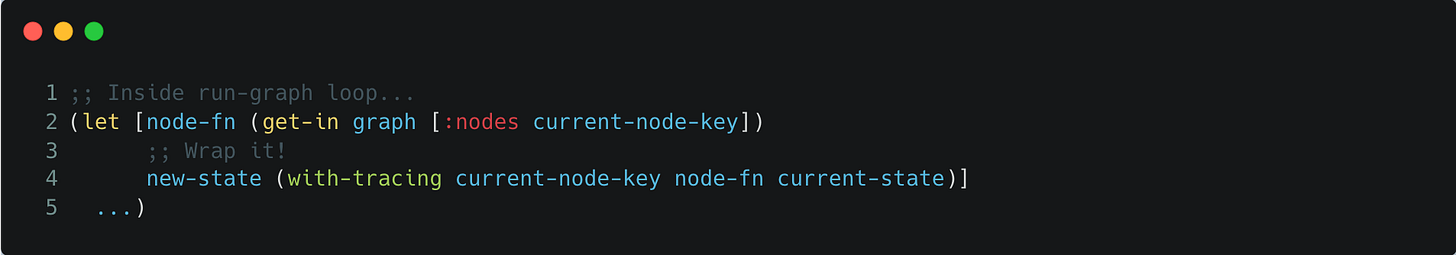

To use this, we simply update our Graph Engine to wrap the node-fn call:

Now, you can connect any visualization tool (like Portal or a custom dashboard) to listen to these taps. You will see exactly how the agent "thought," step by step.

Conclusion: The Power of Simplicity

We started this journey to de-mystify Agentic AI. We looked at complex frameworks like LangGraph, stripped away the layers, and rebuilt the minimal core engine using Clojure.

What did we find?

The “Agent” is just a recursive loop.

The “Brain” is just structured JSON generation (

malli).The “Workflow” is just a map and a state machine.

The “Telemetry” is just a simple wrapper.

By using Clojure, we avoided the “Class Explosion” typical of OOP frameworks. We treated code as data. We utilized immutability to manage state safely without complex lock mechanisms. We built a system that is transparent, testable, and surprisingly small.

Where do we go from here?

This is a functional prototype. To make it a production-grade enterprise platform, we could:

Add Persistence (Postgres) to pause and resume workflows (Human-in-the-Loop).

Implement the Model Context Protocol (MCP) to connect to external tools like GitHub or Google Drive standardly.

Use

core.asyncto handle thousands of concurrent agents.

But honestly? The core logic is already here. The rest is just plumbing.

I encourage you to try building your own tools. Don’t be afraid to look under the hood. Sometimes, the best way to understand the future is to build it yourself.

Maybe we will add those advanced features in a future series. You know, just for fun! :)

The complete code is available on GitHub.

Brilliant breakdown of the core mechanics! The tap> approach for observability is clever tbh, way cleaner than wrestling with logging frameworks. I've run into similar 'class explosion' issues when trying to customize LangChain for edge cases, and seeinghow much can be done with pure fucntions is refreshing.

Absolutely beautiful. Thanks a lot for sharing.