Reconstructing Biscuit in Clojure

Exploring capability-first authorization through a minimal PoC

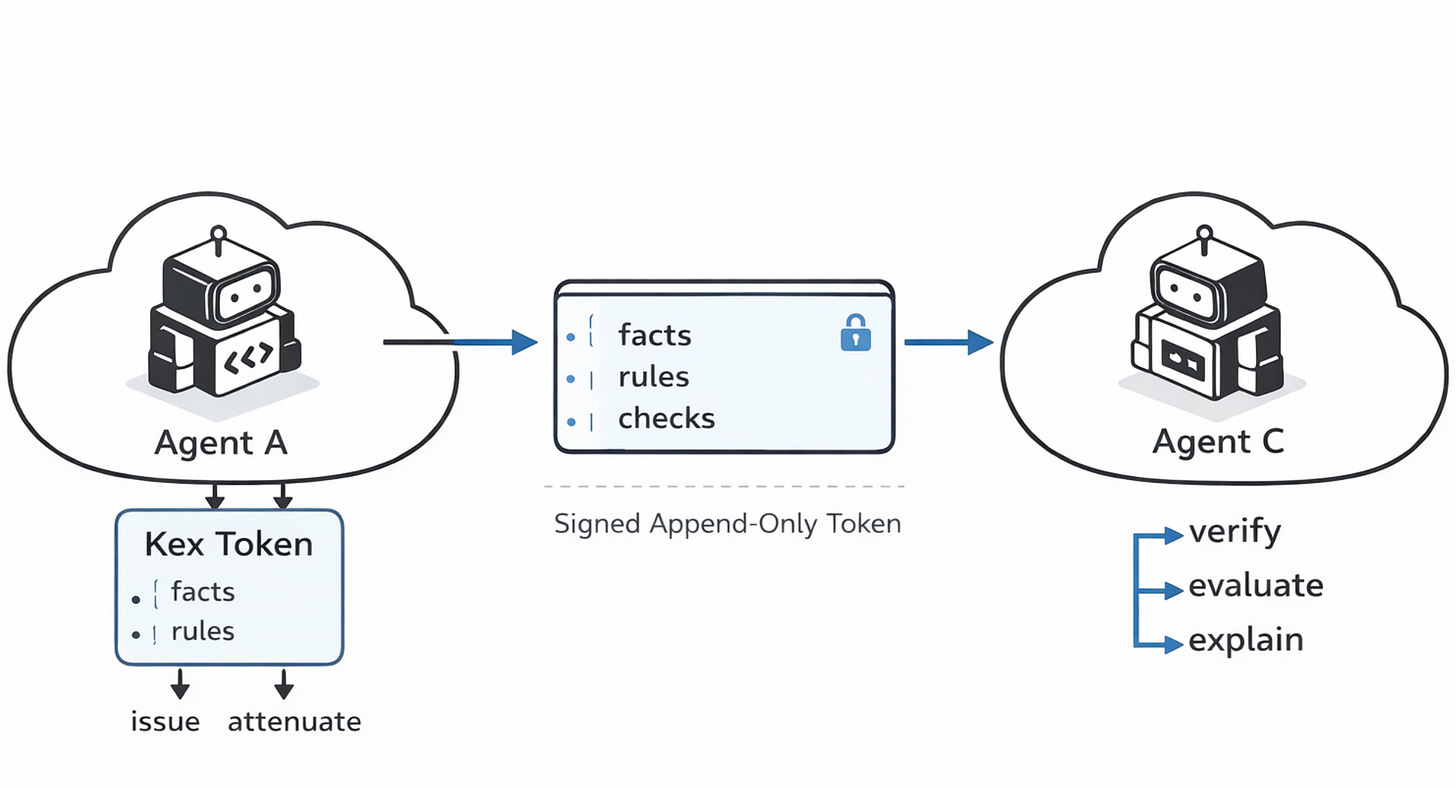

Authority in Agentic Systems

Over the past few months, experimenting with agentic systems, my thinking kept coming back to one question: how does authority actually move between components? That led me to OCapN and structural authority, then to interpreting OCapN in cloud-native architectures. Those articles are below.

Most systems answer this with identity. You authenticate, get a role, and a policy engine decides what you can do. This tends to work well when everything is centralized. But distributed systems can put pressure on this model. Consider two cases in particular.

An agent that needs to make an authorization decision offline. Or an agent that needs to delegate a narrow slice of its authority to another agent, across a service boundary. In both cases, the token has to carry enough information to be evaluated on its own. Identity alone tends not to be enough for this.

This is the tension I wanted to explore: what if authority were something you carry explicitly, rather than something a central engine derives for you?

Two Mental Models

Identity-first: You prove who you are. A policy engine looks up what you are allowed to do. Delegation means giving someone a role. Restricting authority means writing more policy rules.

Capability-first: You carry a token. The token contains the authority directly. Delegation means giving someone a narrower version of your token. In this model, the token is designed to enforce the constraints.

The difference tends to matter in distributed systems. With identity-first, you typically need the policy engine available at the point of evaluation. With capability-first, the token is designed to be self-contained, you can verify it without calling back to a central service.

Biscuit is one concrete implementation of this model. It is a token format where authorization logic, facts, rules, and checks, travels inside the token itself, expressed in a Datalog-style reasoning language

What Biscuit Does

A Biscuit token contains three things: facts, rules, and checks.

Facts are statements about the world. “Alice has the role of agent.” “Bob is an internal agent who owns a web-search tool.”

Rules define what can be derived from facts. “If a user has the role of agent, and a target is a known internal agent, that user can read that target.”

Checks are conditions that must hold for the token to be valid. “This token must verify that Alice can use Bob’s web-search tool.”

When you verify a Biscuit token, each block is evaluated within its own scope. Facts in one block are not automatically visible to another. Checks in a block are evaluated against only the facts that block can see. If all checks pass and all signatures are valid, the token is valid.

Delegation works by appending a new block. You can add facts or checks, but existing blocks cannot be changed without invalidating the token, because each block is cryptographically signed. Because each block’s checks are evaluated in isolation, a later block cannot bypass a constraint set by an earlier one. In Biscuit's design, that guarantee is structural, not policy-based.

There are tradeoffs worth considering, and some of them are discussed in the open questions below. The most immediate is complexity, Biscuit uses a Datalog-style reasoning model. Many developers are not familiar with it. The mental model is different from role-based access control or a tool like OPA. This is a real cost.

Rebuilding the Core: Kex

I wanted to understand Biscuit by building a minimal version of it. Not a full implementation. Not production-ready. Just the core ideas, small enough to inspect.

The result is kex, written in Clojure.

Why Clojure? Because facts, rules, and proofs map naturally to immutable maps and vectors. The whole system stays visible. You can evaluate a token in the REPL, inspect the derived facts, and follow the reasoning step by step.

Facts

A fact is a vector:

[:role "alice" :agent]Facts live inside blocks:

{:facts [[:user "alice"]

[:role "alice" :agent]]}Nothing is evaluated yet. This is just structured data.

Rules

A rule describes how to derive new facts:

{:id :agent-can-read-agents

:head [:right ?user :read ?agt]

:body [[:role ?user :agent]

[:internal-agent ?agt]]}If [:role "alice" :agent] and [:internal-agent "bob"] exist, this rule derives [:right "alice" :read "bob"]. Rules keep firing until nothing new appears.

Kex implements a minimal Datalog engine using plain Clojure data structures. This tends to keep the system easy to inspect, but recursive rules and negation are not supported. That is a deliberate trade.

Checks

A check is a query that must return at least one result:

{:id :can-read-web-search

:query '[[:right "alice" :read "web-search"]]}If the query returns nothing, the token is invalid. In kex, all facts from all blocks are collected first, then all rules are applied to derive new facts, and finally checks are evaluated against the full combined fact set. In the example above, the check is satisfied because the :can-implies-right rule, added in the delegation block, derives [:right "alice" :read "web-search"] from the [:can "alice" :read "web-search"] fact. Biscuit evaluates each block within its own scope, blocks cannot see each other's private facts. Kex does not implement this isolation.

Issuing a Token

The issuer creates the first block. It defines who Alice is and what agents are allowed to do.

(def token

(kex/issue

{:facts [[:user "alice"]

[:role "alice" :agent]]

:rules '[{:id :agent-can-read-agents

:head [:right ?user :read ?agt]

:body [[:role ?user :agent]

[:internal-agent ?agt]]}]

:checks []}

{:private-key (:priv keypair)}))This signs the block and returns a token. The block cannot be changed after this point.

Delegation

A second service appends a new block. It adds facts about what Alice can access, and a rule that derives read rights from those facts. Because kex collects all facts and rules from all blocks into a single pool before evaluation, this block's facts and rules will be combined with the first block's during derivation.

(def delegated-token

(kex/attenuate

token

{:facts [[:internal-agent "bob"]

[:can "alice" :read "web-search"]]

:rules '[{:id :can-implies-right

:head [:right ?user :read ?res]

:body [[:can ?user :read ?res]]}]

:checks []}

{:private-key (:priv keypair)}))A new block is appended. The old block is untouched.

Adding a Check

A third party appends one more block. It adds nothing but a check. This token is only valid if Alice can access Bob's web-search tool.

(def auth-token

(kex/attenuate

delegated-token

{:facts []

:rules []

:checks [{:id :can-read-web-search

:query '[[:right "alice" :read "web-search"]]}]}

{:private-key (:priv keypair)}))Verification and Explanation

(kex/verify auth-token {:public-key (:pub keypair)})

(def decision (kex/evaluate auth-token :explain? true))

(:valid? decision)

(:explain decision)The explain output shows which rules fired and which facts satisfied each check. You can turn this into a graph:

(kex/graph (:explain decision))In kex, authorization tends to become something you can read, not just trust.

What Kex Does Not Do

Kex does not handle revocation, recursive rules, or the full Biscuit serialization format. It is not performance optimized. Do not use it in production.

It also does not fully enforce attenuation. A new block can add broader facts that expand authority if no check prevents it. In Biscuit, block isolation prevents this, a new block cannot see or override facts from another block’s private scope. In kex, that isolation is not implemented.

The full source is available here: https://github.com/serefayar/kex

Open Questions

Building kex made the capability model concrete, but it also made some hard problems more visible.

Revocation and offline verification are in tension. If a token is self-contained and does not need a central service, how do you invalidate it before it expires? Biscuit has partial answers here, but the problem does not go away. It shifts.

Token size grows with each delegation. In systems with deep delegation chains, this can become a practical concern.

Ecosystem fit is also an open question. Most existing infrastructure expects JWT or OAuth tokens. Biscuit does not slot in easily.

Explainability is useful in small systems. Whether it scales to the rule complexity of a real authorization policy is a different question.

And the bigger question: do capability-first models actually solve distributed authorization, or do they mostly reframe it? I do not have a confident answer. Kex is one small experiment in that direction.